By ATISHI MARLENA

This article draws a parallel between the functioning of Delhi Assembly’s Petitions Committee with that of the United States Congress. It first appeared on Firstpost here.

People across the world are familiar with United States’ Congress and Senate committees, as they have often featured in Hollywood movies or Netflix web series like House of Cards – as political scandals are disclosed and investigated through these committee hearings.

While the actual proceedings of these committees may not be quite as nail-biting as the Netflix producers would have us believe, the oversight role played by them is crucial to the DNA of a liberal democracy.

At the heart of democracy is a separation of powers between different institutions such as the legislature, the executive and the judiciary, as well as the checks and balances these institutions keep upon each other. This is what distinguishes democracies from the monarchies that preceded them, where the all-powerful monarch was the law-maker, the decision-maker and the supreme judge, with unquestioned authority sanctioned by him or her being the representative of God on Earth.

As democracies came into being, it was the ‘will of the people’ – not of the monarch – that came to occupy centre-stage in the political system. Each institution of the government had to be geared towards fulfilling this mandate, as well as keeping a check on all other institutions.

Towards this end, the oldest democracy in the world, the United States, has developed a system of oversight of the Executive by the Senate and Congress Committees. These committees are important since they ensure that the Executive branch of the government is complying with legislative intent.

Given a large bureaucracy, it becomes essential to ensure that the ‘will of the people’, as put forth by their elected representatives, is actually implemented and doesn’t only remain on paper. These committees are a way of ensuring checks and balances of the elected representatives, upon the president and the federal government.

While committee enquiries into high profile cases like the Watergate scandal have made international news, the Congress and Senate committees are looking into the implementation of bread-and-butter policy matters like health, education reform or the expenditure of different agencies, on a regular basis. These committees have ensured the accountability of the president and the federal bureaucracy.

An interesting phenomenon can be seen in India’s national capital, where similar committees of Delhi Assembly have started becoming active in the last few months. They have been in the news as they have summoned government officials, been on the streets of Delhi to see whether the storm-water drains have been de-silted and inspected hospitals in the middle of the night to see whether free medicines are available 24X7.

An observer of Delhi’s politics would be justified in asking why the process of legislative oversight has been brought into action more than two years after the current Legislative Assembly was elected. The cause for this lies in the peculiar situation in which the elected representatives of this city find themselves.

Delhi is a Union Territory with a legislature, which was brought into being by inserting Article 239AA into the Constitution. The leader of the single largest party is invited to form the government by the Lieutenant Governor (L-G), and the chief minister chooses his Council of Ministers.

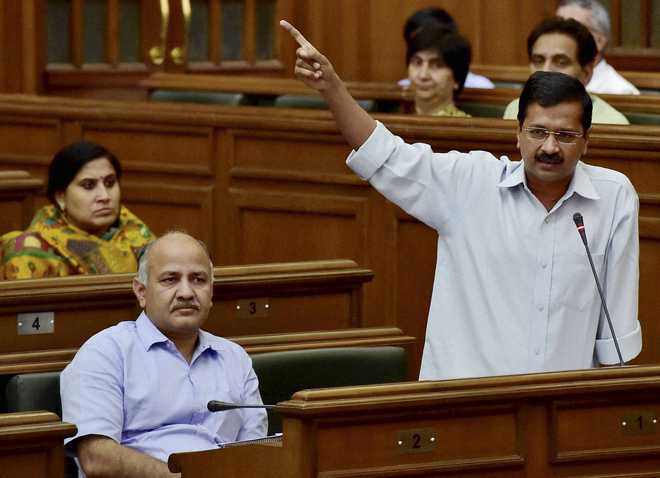

The Council of Ministers is then supposed to execute the ‘will of the people’ via the bureaucracy. The Aam Aadmi Party came to power in February 2015 with a thumping majority, winning 67 out of the 70 seats in the Legislative Assembly. However, two things changed the way the Delhi Government had been functioning since 1991 (when it came into being): First, a home ministry notification of May 2015 – which was upheld by the Delhi High Court in August 2016 – took away ‘Services’ from the elected government and handed it over to the unelected L-G.

This meant that elected government now had very little control over the bureaucracy. Second, the high court verdict stated that the unelected L-G – and not the elected government – is the ‘government of the National Capital Territory of Delhi’. While the Aam Aadmi Party government challenged this decision in the Supreme Court, a question remained before the elected representatives: how would they fulfil the ‘will of the people’, if the government was controlled by an unelected L-G and the bureaucrats were not accountable to them.

And herein lies the rationale behind the activation of Assembly Committees and the process of legislative oversight: that the legislators needed to ensure that the bureaucracy is working to fulfil the policy mandate for which these MLAs were elected by the people of Delhi. And this has brought the Assembly Committees out on the ground, to ensure an effective bureaucracy and functional government departments.

Delhi-ites experience water-logging every monsoon, yet government files show that comprehensive de-silting happens every year. To find the reasons behind this annual crisis, Delhi Assembly Petitions Committee spent days inspecting storm-water drains to see whether the de-silting claimed on files by government departments had actually happened. And the results were quite horrifying. In the report presented to the Delhi Assembly, the Committee showed photographic evidence of how the drains that were supposed to be 100 percent de-silted, were full of garbage and sediments. So much for the authenticity of bureaucratic claims.

While Assembly Committees make late night visits to hospitals to examine their effective functioning, go through tender documents of Delhi Jal Board to ensure no corruption took place in the awarding of contracts and recommend action against erring officials, it is important to realise that this experiment in legislative oversight goes beyond these bread-and-butter governance issues.

It is an experiment in ensuring the accountability of an unelected Executive and an unresponsive bureaucracy; it is an experiment in ensuring that the ‘will of the people’ is implemented through multiple institutions of our democracy.

Atishi Marlena is a member of the Political Affairs Committee of the Aam Aadmi Party and an Advisor to the Deputy Chief Minister of Delhi.

1 Comment